Esoteric Maoism

The Influence of Hermetic and Occult Traditions on the Theory and Practice of Mao Zedong

On October 1, 1949, the Mandate of Heaven, which had been the object of intense conflict for decades among warlord cliques, Chinese nationalists, and the Japanese empire, would finally be reclaimed for the first time since the fall of the Qing Dynasty with the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China. The Mandate was reclaimed not by any imperial bloodline, but instead by revolutionary Marxists, the Communist Party of China under the leadership of one of the most influential guerilla fighters of all time, Mao Zedong. In leading the Communist partisans to victory in the long fought conflict and in his role as party chairman overseeing the emergence of China as a great power, Mao Zedong appears to us as a world historical figure, the leader of the movement which finally ended the Chinese Century of Humiliation, comparable to Qin Shi Huang in uniting China millennia ago or Napoleon Bonaparte in totally reshaping the politics of Europe. These comparisons are not exceedingly controversial, but in this piece I understand that I will likely ruffle some feathers when I propose that Mao Zedong is perhaps best understood as comparable to the legendary Hellenic figure of Hermes Trismegistus.

Hermes Trismegistus, for those unfamiliar, is a mythological entity with multiple layers. On the surface he is a synthesis of the Egyptian god of wisdom and writing Thoth and the Greek god of boundaries and travel Hermes, but he was also considered by Medieval and Early Modern writers and thinkers to have been a mortal occultist of incredible influence responsible for the intellectual school of “Hermeticism,” a tradition which remains extremely influential among most modern occultists. When we study the fundamental principles of Hermeticism common to the various texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, we find a pattern which resembles the philosophical foundations of Mao Zedong’s interpretation of Marxism, particularly as found in On Contradiction. The common Hermetic refrain, “As Above, So Below,” and its elaboration that “everything is dual; everything has poles; everything has its pair of opposites,” suggests the central nature of the “Unity of Opposites” at the heart of the occult philosophy, finds its parallel in Mao’s conception of the “universality of contradiction.” Just as Mao asserts that “contradiction is the basis of the simple forms of motion… and still more of the complex forms” and that “there is nothing in this world except matter in motion,” the Hermetic texts inform us that “nothing rests, everything moves, everything vibrates,” and “everything flows out and in.” The universal role of opposing forces within objects and the constant movement and development of objects as a result of these forces, which might also be phrased as the universal role of contradiction, forms the basis of both the Hermeticist and the Maoist worldviews. It appears to us unlikely that Mao actually studied or was directly influenced by the Hermetica, but that there are obvious sources for these parallels. The common thread of dialectical monism serving as the basis for Hermeticism, as well being as a key component of the historical Chinese philosophies which Mao would have studied and used as a framework for his understanding of Marxism is one source of this convergence of views, but perhaps much more importantly is the way Mao was actually the student of the most refined and advanced school of Hermeticism: Hegelianism.

Marxists cannot escape the overwhelming shadow cast by the thought of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: even as Marx turned his foremost intellectual influence “on his head,” he remained by nature a Hegelian thinker. Throughout Hegel’s writings, the occult influences are abundant if you know where to look as Glenn A. Magee makes clear in his work Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. Hegel’s conception of history as God coming to know Himself through humanity’s contemplation and development is a decidedly Hermetic worldview, his Phenomenology of Spirit is structured as an initiation into esoteric knowledge similar to that of the mystery schools and Rosicrucian societies, his Science of Logic draws extensively on the revered occult Hebrew tradition of the Kabbalah, one of the many schools of wisdom which Hermeticism draws from, and his Philosophy of Nature is based on Hermetic conceptions of alchemy. As a whole Hegelian thought appears then as the height of Hermeticism, having brought together a disparate intellectual tradition into a coherent single philosophy. Furthermore through the influence of Hegel’s philosophy and conception of history, Karl Marx and by extension Marxism is in turn part of the Hermetic tradition even if they do not conceive of themselves as such. Not only that, by taking Hegel the greatest Hermetic thinker, and adapting his ideas to understand the nature of political economy, the actually existing process of alchemical transmutation through which labor is transformed into capital, Marxism appears to us as Hermeticism synthesized to a higher stage and the pinnacle of Occultist thought.

If we accept this understanding of Marxism as the heightened form of Hermeticism, then it becomes obvious that Mao Zedong is an occultist of incomparable talent and power both in his intellectual contributions to Marxism and his role in implementing the ideas of Marxism into practice. In describing the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the most extensive implementation of the dictatorship of the proletariat in history, Mao asserted that “a great chaos will lead to a new order,” reflecting the arcane Masonic motto of Ordo ab Chao, as well as the alchemical process through which metals such as lead are broken down into base matter so that this in turn might be reconstructed into gold. In this way the GPCR was not just a continuation of Chinese Communist Revolution throughout the early 20th century, but also a mass magick ritual to reorder society on an unprecedented scale through the implementation of the Mass Line. To draw upon the doctrines of a more conventional occultist, Aleister Crowley, magick is “the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will.” In this sense, Maoism correctly implemented, especially in the case of the GPCR, is magick conducted in conformity with the will of the masses. The Party cannot be a tool for the satisfaction of base desires of the apparatchiks, but instead an instrument of the True Will, the occult order that advances history through service to the proletarian masses while at the same time initiating them into itself.

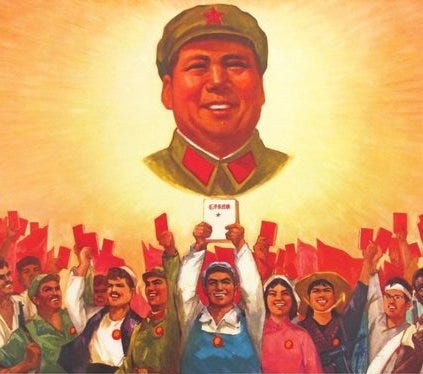

Beyond the implementation of the Mass Line as occult ritual, esoteric symbolism drawn from Chinese philosophical dualism pervades the propaganda of Mao-era China in its exaltation of the Chairman that further emphasizes the dialectical monism of the Party and the Masses. Mao is frequently depicted as a “Red Sun'' whose rays of knowledge and liberation shine down on the masses, making him into a masculine solar figure associated with the “Yang.” This concept is traditionally paired with its counterpart, the feminine and lunar “Yin'' associated with the waters, which Mao was often transposed against such as in his role as the “Great Helmsman” leading the masses, or simply in his penchant for taking regular swims in the Yellow River. This Yin-Yang dualism, especially common in Taoist spiritual practices, is even alleged by anti-communist biographers to have been a part of Mao’s private life. These lurid claims assert that the Chairman was involved in explicitly esoteric practices with numerous women. This Taoist ritual sex, which finds parallels in Tantric sex practices and the Hieros Gamos of Western Asia, centered around the retention of semen (the fiery Yang) while exciting vaginal secretions through arousal (the watery Yin) as a means to extend the Chairman’s life. Regardless of the truth of such assertions about Mao’s sexual proclivities, the “unity of opposites'' he sought to put into practice bringing together the Party and the Masses finds parallels in Chinese esoteric traditions as well as in Bataillean conceptions of the Sun as the engine of the general economy and the circulation of energy. Just as the Sun provides its energies without benefit, as luxury, to all living things which feed on it, so Mao gave the simple command to the cadres to “serve the people,” to provide for their needs without compensation to bring them into the fold. Indeed, despite the contemporary People’s Republic of China’s significant deviations from Maoist theory and practice, their approach to economic diplomacy is clearly in accordance with the principles of the “Solar Economy,” channeling those excess energies which cannot be used productively at home into “luxury” developing the infrastructure of other nations through the Belt and Road Initiative to cultivate goodwill follows this same model, the solar “Yang” of China reconciling itself with the watery “Yin” of the nations of the world.

Like most great occultists, Mao Zedong was engaging in a massive undertaking for most of his life that was ultimately left incomplete. In the practice of alchemy, the goal of an alchemist is the creation of the filius philosophorum, or “Philosopher’s Child,” the union of solar and lunar principles represented by the figure of the Divine Hermaphrodite. Similarly, the revolutionary seeks to achieve a “unity of opposites” in the resolution of social contradictions which cannot be addressed except through struggle. In both alchemy and revolution, this is a movement towards completing the Great Work, the process through which the conflict between antithetical forces brings about a climax and a new force is able to emerge. Not only did Mao conceive of the Great Work as the achievement of world communism, but the contemporary Chinese Communist Party draws deliberate parallels to the classical concept of the Datong or Great Unity, and well as the Confucian idea of the Harmonious Society, ancient parallels to the Marxian end goal. But it can also be argued that Mao saw further than the Great Work as merely achieving a more “harmonious” social order, but something even more wonderful. Just as Hegel conceived of the Hermetic “end of history” as a grand cosmic revelation, in which God would reach gnosis through the medium of humankind, Mao also saw the transcendence of the existing world as the inevitable outcome of the dialectic process. In the Talk on Questions of Philosophy, he specifically asserted that:

“The life of dialectics is the continuous movement toward opposites. Mankind will also finally meet its doom. When the theologians talk about doomsday, they are pessimistic and terrify people. We say the end of mankind is something which will produce something more advanced than mankind. Mankind is still in its infancy.”

In the occult practice of dialectics, from Hermes to Mao, the goal is to transmute the human collective into something of a higher grade, something which can only be achieved through mass initiation into the mysteries and a willingness to dissolve the existing order into its base components before it is reconstructed into something new and greater.

When we consider such things, it is important to caution ourselves against falling into the trap of heroic or “Great Man” theories of history. Regardless of his talent as a Marxist theorist and revolutionary leader, Mao was only capable of what he accomplished because of both the material circumstances of his lifetime, and the work of countless cadres, proletarians, and peasants who made the success of the Chinese Revolution even conceivable. Mao Zedong was not without flaws, ill-conceived decisions, and failures which we must still contend with, but he appears to us as a “Great Man” of history primarily in the ways in which he lived by that principle of “Serve the People” and upheld the Mass Line which worked to close the gap between the Party and the Masses, the Sacred Marriage which can realize that Great Work, World Communism. It is for these reasons that Marxists should think twice before dismissing the occult and Hermetic, considering the ways in which it manifests in Hegel, Marx and Mao’s writings. Through the study of Hegel’s hermetic influences, as well as the occult nature of the socialist practices implemented by Marxist leaders such as Mao Zedong, we can come to synthesize an Esoteric Maoist approach to mass politics which achieve that “unity of opposites” between the Party and the Masses, aligning both with their True Will and their potential to bring about a new order out of the chaos of capital and empire.